Where Everything Goes (For Now)

006. How We & the Land Are Shaping Our First Draft

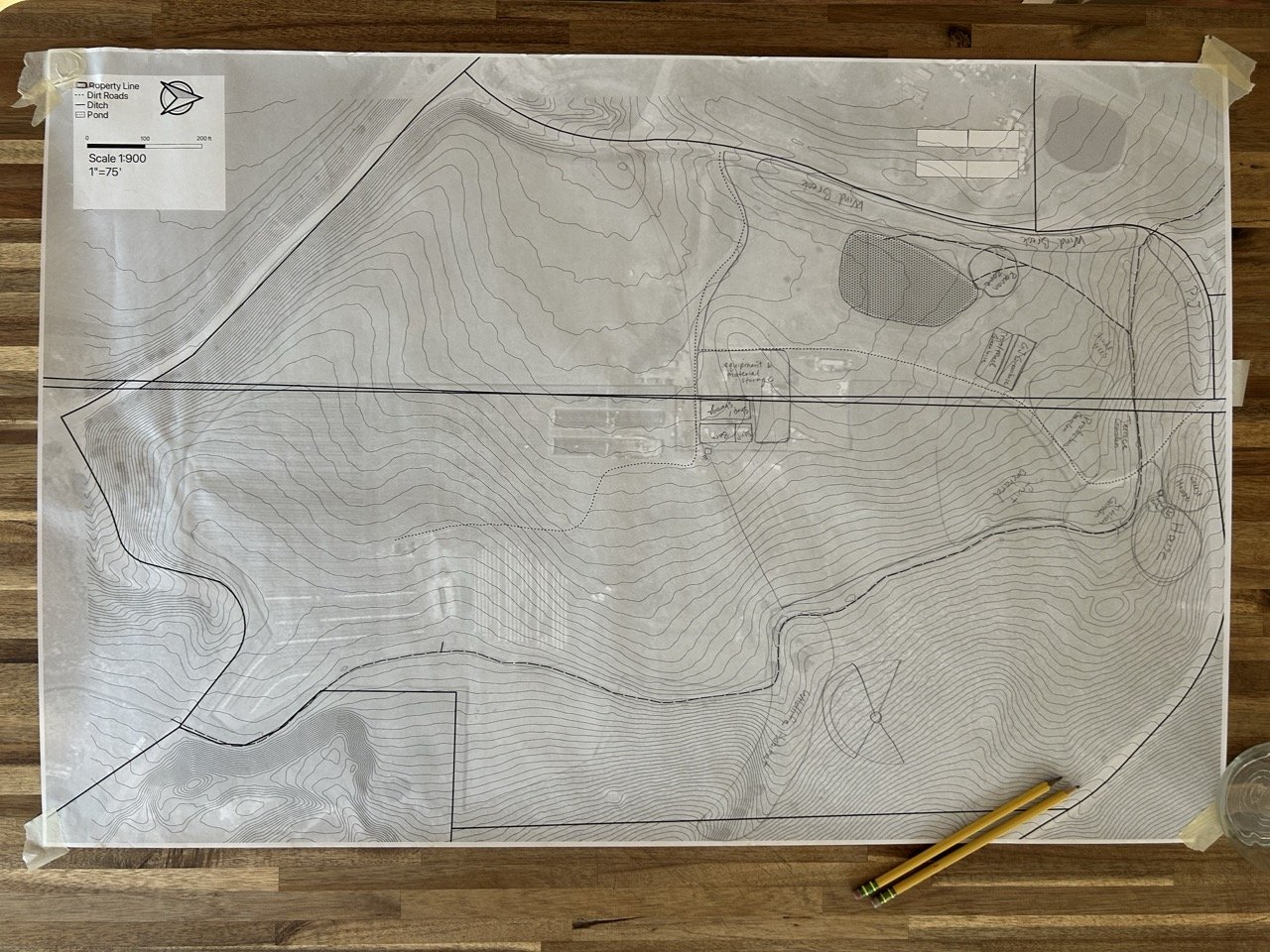

We sat down at the butcher block kitchen island—property map taped down at the corners, pencils sharpened, notebooks stacked off to the side, our list of programs (the activities, structures, and living things that will make up our homestead) marked with 1–5 to indicate their priority on a loose sheet of torn-out notebook paper.

We started with the 1s and talked through where each program would go. Some were influenced by other programs, and so our discussions circled around as one by one we marked up the map with lines, squares, and bubbles—making decisions based on the work we’ve done thus far to shape our vision and goals, and on some key drivers from the land.

What follows are some of the biggest influencing factors in designing our homestead site, and an overview of our working homestead design.

The Influencers: Land, Sun, Water, and Vision

Slope, aspect, and points of view

If you were to walk from the center of the west edge of the property straight across to the east edge, you'd gain 110 feet of elevation. Two-thirds of that walk would be a very gradual uphill stroll, rising 40 feet over four acres. East, northeast, and north from this point on the property, the slope rises more quickly, forming a somewhat steep hillside of sagebrush, juniper, basaltic rocks and, magically, thick carpets of moss tucked beneath these drought-tolerant desert shrubs.

The hillside, which flows down from that northeast point, accounts for about a third of the 44 acres. Its bend creates a refuge of calm from the wind—which surprised us by coming from the north/northwest during our last few visits. Deer and elk droppings are everywhere, and their footprints scatter the hillside. The buttes form a natural drainage into the only speck on the property with trees—oak trees—where oak leaves cover the ground right next to a bend in the irrigation ditch, forming a spot that feels nostalgic and so serene.

With each small rise in elevation as you climb up the gentle slope of the hillside, mountain summits begin to pop up from behind the neighboring hills, and so the faraway landscape changes drastically depending on your vantage point.

Looking south, from a high point on the hill

All in all, the land is angled downward toward the southeast and spills down onto the road directly south, gifting us a south-facing aspect that opens up lots of opportunity for harnessing solar energy.

View from east of the ditch, looking north

Irrigation

Resilience being an important value for both of us, we favor simple and reliable methods of irrigation. The land’s topography, historical usage, and water rights all lend themselves well to flood irrigation.

The ditch runs across the property from the southeast corner, across the bottom of the hillside to the north end of the property, then makes a 90-degree bend to the northwest. Here it forks into two: the main channel continuing straight to the northwest corner of the property where it leaves us, and the side channel bending again toward the south, where it fills the pond (which was built for irrigation water storage) and can continue further southward in an unlined ditch along the west edge of the property.

(If you find yourself repeating Never Eat Shredded Wheat—or Soggy Waffles, if that’s how your mama raised ya—while reading every sentence of this post, know that I am saying it to myself while writing every one. I actually love shredded wheats frosted with sugar and prefer my waffles sufficiently soggy with butter, but hey, it stuck anyway.)

Other irrigation opportunities on the property include massive (moveable) storage tanks and another rectangular, 15-foot-deep, plastic-lined hole we’ve named The Death Trap, dug higher up on the property with gravity in mind. Systems like this—like flood irrigation—will allow us to irrigate without running pumps, which are both resource (electricity) intensive and reliant on the grid, making them less aligned with our operating values.

The ditch is flowin’!

Vision, values, and goals

I hope you don’t get tired of those words, because you’re going to read them a lot over the course of Desk to Dirt in the years to come. Right alongside observing and listening to the land, our biggest influencers are our vision, values, and goals. These will shape and be shaped by the land—and our interactions with it—along the way, but they’re the third leg of the stool when it comes to the major forces guiding our decision-making.

[Check out this post to read how we defined ours.]

The Map: What’s On It and Where

Starting with programs marked with a #1 priority, we made our way down the list—meandering at times—and drew our programs onto the map. I had to first ask Cooper to agree not to scribble and mark up the paper until we talked a program through and landed on its location (even though we were using pencil), because I’m anal and wanted the map to stay pretty and organized. He agreed because he loves me.

You can see for yourself on the map below where everything has landed, but there are some programs worth elaborating on—stories, if you will, about how they ended up where they are (at least in pencil, at least for now).

Moving the greenhouse frames

Throughout contracting, in my earlier sketches of the site map, and in our conversations, Cooper and I imagined the greenhouses staying where they are: smack dab in the middle of the property. Far from anywhere we’d build a house, far from the pond where we know we’ll spend lots of time. In permaculture terms, our Zone 1—the most frequently visited area of a site—would be more like suburban sprawl than a walkable European village.

Besides their distance from the property's future hub, the greenhouses also sit right in the path of flooding on the entire southern half of the property. We’d need to do some major earthworks to change the flow of water, and then it’d be a fight against physics to redirect it inward again after swerving out around the greenhouses.

Once we accepted our fate, the possibilities opened up to us.

Four 30’ x 90’ greenhouse frames with lots of cleanup work needed

Since the area in the center of the property has already been heavily trafficked and used for storage and operations, we're designating that area for continued equipment and material storage. We’ll move two of the four greenhouse frames there—not a hundred yards from where they currently sit, but far enough to clear that flood path while still taking advantage of the compacted dirt and gravel and the adjacent bend in the gravel road.

The other two greenhouses will go between the pond and the gardens.

Three gardens and an orchard

Over the years, Cooper and I have mixed and matched our farming styles. He loooves efficiency and speed; I prefer a pace sloths would wink at. He likes straight rows and good spacing between plants because he likes to hula hoe and use the tractor; I’m averse to gear generally, find it hard to even put gloves on, and prefer my garden to be layered, wild, and whimsical.

On our farm today, we’ve tried each other’s styles. We’ve compromised here and there. Sometimes we agree, sometimes we roll our eyes at each other (but only when we know the other one is watching—silent eye-rolls kept to oneself is not a recipe for loving partnership that I want to try. But an overly dramatic one followed by me agreeing to do something Cooper’s way because it’s completely logical? What better way is there to say I love you? Okay, fine, it’s only me that does the eye-rolling! Let’s move on.)

In my dreamland, I’m up close in my garden, doing everything with my hands, tending in that meditative state and inspired by the dill towering over onions and a sweet pepper while strawberries wind their way along the ground. I’m sitting cross-legged or squatting or on my knees—low—feeling like a forest fairy.

But we also want a cellar full of carrots, onions, potatoes, winter squash. Cupboards of dried peas and beans. Storage crops.

So, above the two food-producing greenhouses will be three garden areas:

A production garden with row crops

A terrace garden along the northern hillside for perennials

A kitchen garden with greens, tender herbs, flowers, and specialty crops

...plus a fruit orchard.

Dwelling

Above the gardens, outside the fenced area and above the ditch, will be our home. We’re a few years away from building a house. This location, nestled in the bend of the hillside, offers protection from the wind. It’s south-facing, so we’ll be able to plan a house that uses lots of passive solar. And from a future second story, views of far-off mountaintops start to appear.

The pond, windbreaks, and riparian zone

The pond, with its leaks and steep edges, is nonetheless established just below the bend in the ditch, where the small tributary will branch again—into the pond when it’s ready to be filled, and down along the west edge of the property. The area between the first fork in the ditch to the second creates a natural wet place, which we’re thinking of as the riparian zone. Here we can plant water-loving plants like willow and fern.

The water flowing down the west edge of the property will quench a windbreak of trees like spruce, fir, and birch before finally leaving the property to find the next place it can spread and sink into the ground.

Designing for wildlife

The land currently doesn’t boast a robust habitat for wildlife, but there is some nonetheless. So far, we’ve seen—or seen signs of—elk, deer, blue canaries, crows, hawks, and owls. I expect bears, coyotes, mountain lions, foxes, rabbits, and maybe even wolves have set foot.

As we plant trees, build soil, and facilitate more life around the pond, we hope more birds, frogs, four-legged creatures, and critters too small to see will call the land home or migrate through. Keeping our agricultural practices chemical-free and fostering diversity is not just about keeping our own bodies healthy but also the habitat of all these living things.

But it’d be delusional to claim righteousness. We are putting up a fence—one tall one around the barn, orchard, pond, greenhouses, and gardens—precisely to keep those bigger mammals from eating our food. We are designing a human-centered, food-producing ecosystem above all.

However, there is lots of opportunity to support the big wild animals outside of our fenced area—ensuring the Death Trap doesn’t become a death trap, and the ditch liner doesn’t ensnare any deer or elk. Planting nut- and berry-bearing trees and shrubs, and more oaks, near the oak trees at the basin of that natural drainage. Planting pinyons and junipers on the hillside, which can likely survive, once established, on only water that comes from the sky or snowmelt. Creating safe access to drinking water and sheltering spaces.

Integrity Through Action

Having and executing a vision can be an egotistical thing. Perhaps, it must be. You see something in your mind and have the gall to make it real. What lens do we have other than the one that comes from inside and allows us to see and interact with the world?

All of the experiences and interpretations life has offered thus far have informed my vision for our homestead, just as Cooper’s informed his, and just as yours inform your vision. But in bringing our homestead vision to life, we must also observe the land itself, the life already on it, its recent and not-so-recent history, and design with it. Otherwise, we are just imposing ideas onto a thing, making that thing, in the process, voiceless, objectified. And it won’t just be the land that suffers from that dynamic, but all the living creatures—including us.

We are designing a place that we believe will support a lifestyle that feels right to us. In turn, our lifestyle will support a place. It is all an attempt to be in integrity—to live in alignment, in honor, of what the world has taught us. To be a part of nature and not separate from it.

Let this map—printed in large format at a store next to a gas station by a woman operating machines run on fossil-fuel-powered electricity—be the start.

TLDR;

Start With a Map and a Vision. We didn’t just sketch where things should go—we worked from values, topography, and lived experience.

Slope, Sun, and Water Rule the Design. Our layout follows the land’s natural contours, sun exposure, and flood irrigation paths.

Compromise Is Part of the Process. From greenhouse placement to garden style, we’re learning how to design together without bulldozing each other.

Not Just for Us. While the fenced area is human-centered, we’re making space for wildlife, too—planting for habitat and keeping our systems chemical-free.

Design Is a First Draft. This map isn’t final—it’s our best attempt at integrity, sketched in pencil and shaped by every walk across the land.